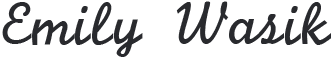

Covid-19 and Fragile Contexts: Reviving Multilateralism’s Promise to ‘Leave No One Behind’

The covid-19 pandemic is projected to cause up to 3.2m deaths in fragile contexts. Low-income countries and fragile states are at risk of being disproportionately affected because they have the least resources and infrastructure to grapple with the pandemic’s dire health and economic repercussions. While protecting the health and safety of those most in need is the collective responsibility of the multilateral system, its response to covid-19 has been strikingly slow, ineffective and underfunded. Failure to mobilise the rapid, co-ordinated action required to contain the virus has resulted in nearly 900,000 deaths on a global scale. It has also caused devastating disruption to the lives and livelihoods of billions of people and precipitated a rollback of hard-fought progress towards global development goals.

This report aims to investigate the contributing factors to the multilateral system’s failure to protect fragile populations from the worst impacts of covid-19. Drawing on comparisons with previous global crises, it will evaluate the pivotal response failures across three areas: a vacuum of global leadership; insufficient funding; and a lack of global co-operation. Lastly, it will outline seven solutions that could help global players to navigate covid-19 more effectively in the near term and strengthen collective preparation for future global crises. Its key findings include:

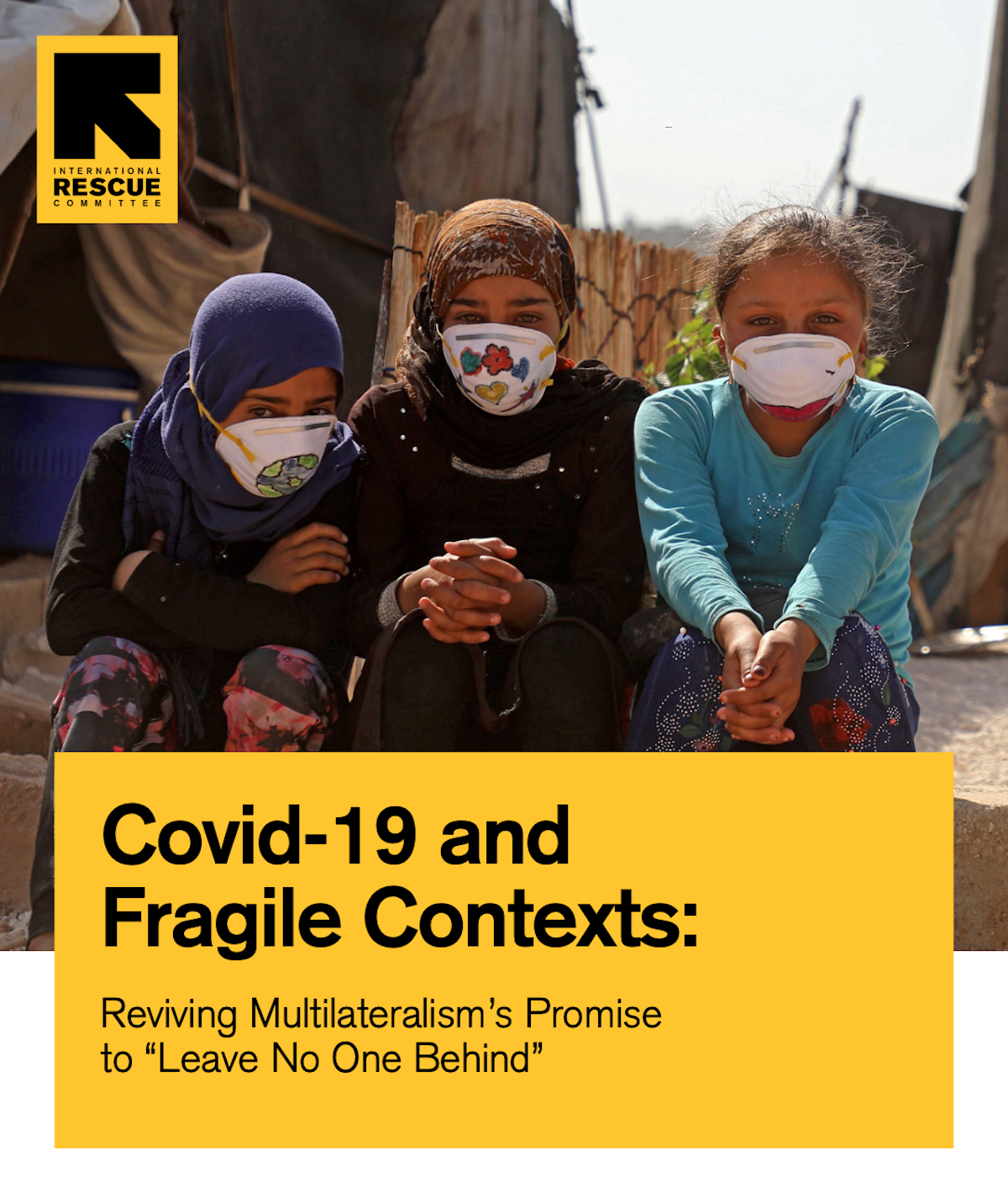

- Multilateralism has broken its promise to the world’s most vulnerable. Rather than mobilising quickly and acting decisively to contain the outbreak, the early global response to covid-19 has been categorised by an absence of leadership, an inadequate fiscal response and a lack of co-operation and information-sharing. Stronger political will and international co-operation frameworks are required to mitigate the pandemic’s adverse effects on lives and livelihoods globally, and in fragile settings in particular.

- Nationalism, interstate competition and political instability fractured the foundation of the multilateral system, leaving many countries to “go at it alone”. When the pandemic hit, some of the world’s most powerful nations retreated from their typical leadership roles. Pivoting inwards, they prioritised the safety and security of those within their borders: travel bans were enforced, information-sharing was neglected, export restrictions were implemented and WHO recommendations were ignored. Despite the multilateral mechanisms in place to navigate global public health emergencies and address their economic, social and political repercussions, heightened geo-political tensions and rivalries between China, Russia and the US at the UN Security Council in particular led many countries to adopt a unilateral approach.

- While countries have allocated an almost unprecedented US$8trn in domestic economic stimulus packages, financing for the global health emergency response has been slow and inadequate. As of September, just 25% of the US$10.37bn Covid-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan was funded, with just 18.7% going to NGOs. More broadly, just 11% (US$1.1bn) of the US$9.9bn covid-19 health funding pledged to date has been disbursed.

- Deficiencies in communication and co-ordination have hindered effective crisis response in fragile contexts. Insufficient data availability in fragile contexts due to limited laboratory and testing capacity combined with inadequate data-sharing practices have made it difficult to put together a truly global picture of the extent of the covid-19 crisis. Despite its mandate to co-ordinate responses to global health emergencies, many countries have also diminished the credibility and effectiveness of the WHO by flouting its guidance and recommendations. Examples of collaboration among scientists, however, show that models for better co-operation are possible.

- Government leaders, policy makers and humanitarian actors must take co-ordinated, collective action to navigate covid-19 in the short term and mitigate its negative impacts in the long term. This will require the revival of commitments to multilateralism’s promise by recognising that collective problems require collective solutions. This includes short-term action as well as long-term reform to strengthen the ability of the multilateral system to respond to both the current pandemic and future crises.